Architecture

Exploring the Craftsmanship and Design of Hegra's Ancient Monuments

The necropolises of Hegra are a remarkable testament to Nabataean civilization, revealing a complex variety of funerary practices and architectural styles. Each tomb tells a different story, highlighting the importance of social prestige in Nabataean culture.

The Evolution and Significance of Nabataean Tomb Architecture

The types of tombs range from simple pit tombs, covered by stone slabs and protected by water-diverting channels, to more elaborate tumuli tombs, characterised by piles of stones and towers, dating between the 1st century BC and the 3rd century AD.

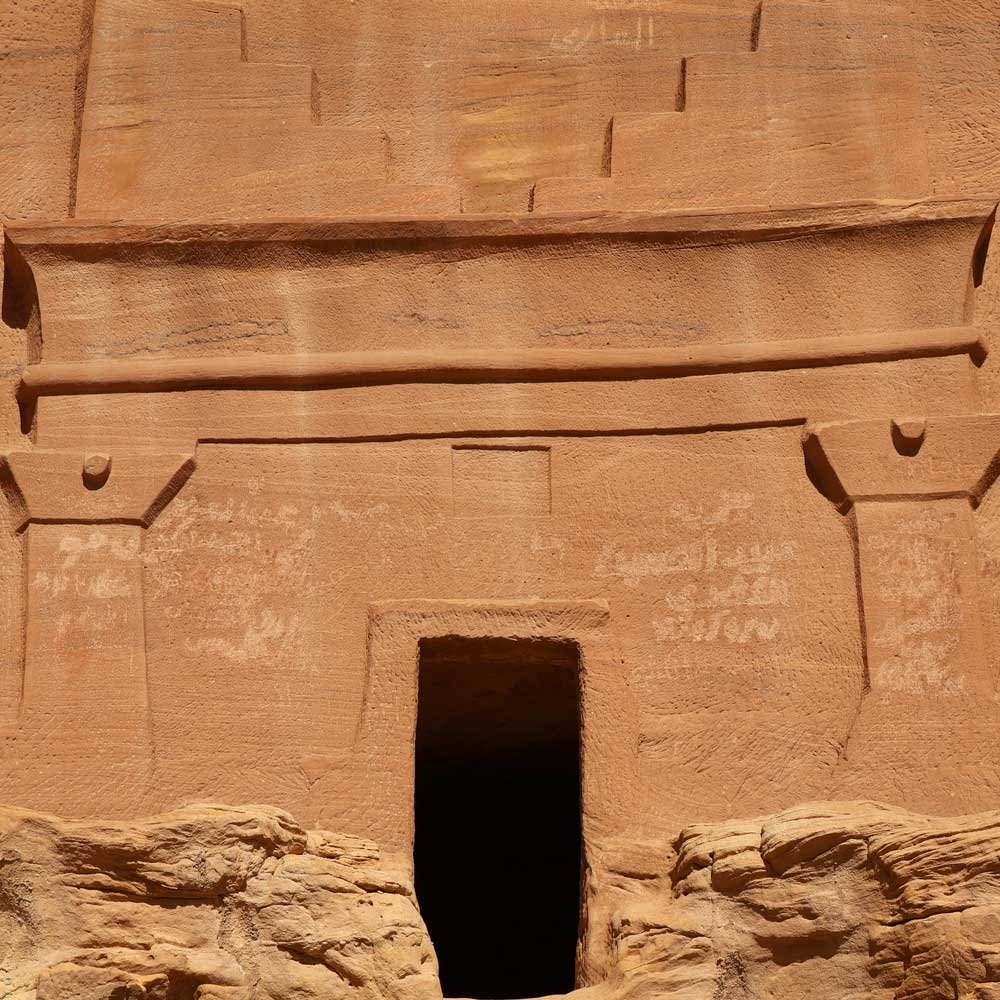

The monumental tombs, carved into the sandstone of Hegra, represent the pinnacle of Nabataean funerary architecture. These imposing structures, mainly dating to the 1st century AD, are decorated with elaborate facades that display Egyptian, Greek, and Roman influences. Nabataean Aramaic inscriptions on the tombs provide valuable information about the society of the time, revealing details about high-ranking individuals and Nabataean legal practices.

Types of Tombs at Hegra

The tombs of Hegra are distinguished by the variety of their decorations and architectural structures, reflecting the social prestige of Nabataean families. Among the main types identified are:

Tombs with one row of crowsteps: 12 tombs featuring a single row of crowsteps at the top, a distinctive and symbolic element.

Tombs with two rows of crowsteps: 14 tombs characterised by two rows of crowsteps separated by an attic.

Tombs with half-crowsteps: 8 tombs with a cornice formed by two half-crowsteps on an Egyptian-style cornice.

Proto-Hegra Type 1 Tombs: 24 tombs with pilasters and a crown consisting of two symmetrical half-crowsteps resting on an Egyptian-style entablature composed of an architrave and Egyptian cornice.

Proto-Hegra Type 2 Tombs: 12 tombs similar to Proto-Hegra Type 1, but with an entablature enriched by a frieze.

Hegra Type Tombs: 15 tombs similar to the Proto-Hegra type, but with two entablatures separated by an attic.

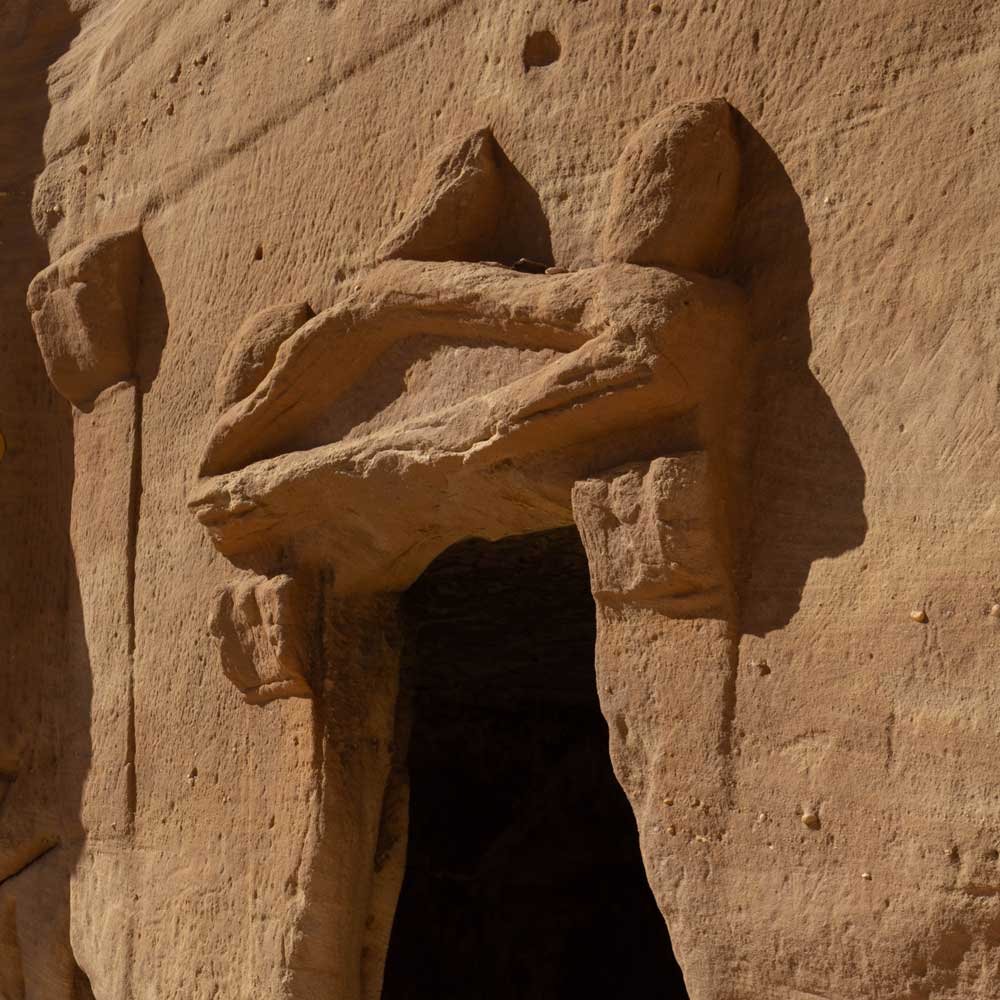

Arched Tomb: A unique example with an arch as a crowning element.

In addition to these decorated types, there are also simpler tombs with undecorated facades, some of which are incomplete. Research has shown that these tombs were not only burial places but powerful symbols of status and prestige for noble families. Hegra demonstrates the importance of monumentality and architectural decoration in Nabataean culture, showcasing the engineering and artistic skills of the Nabataeans and their ability to thrive in a desert environment, leaving a cultural legacy of inestimable value.

Stone Working

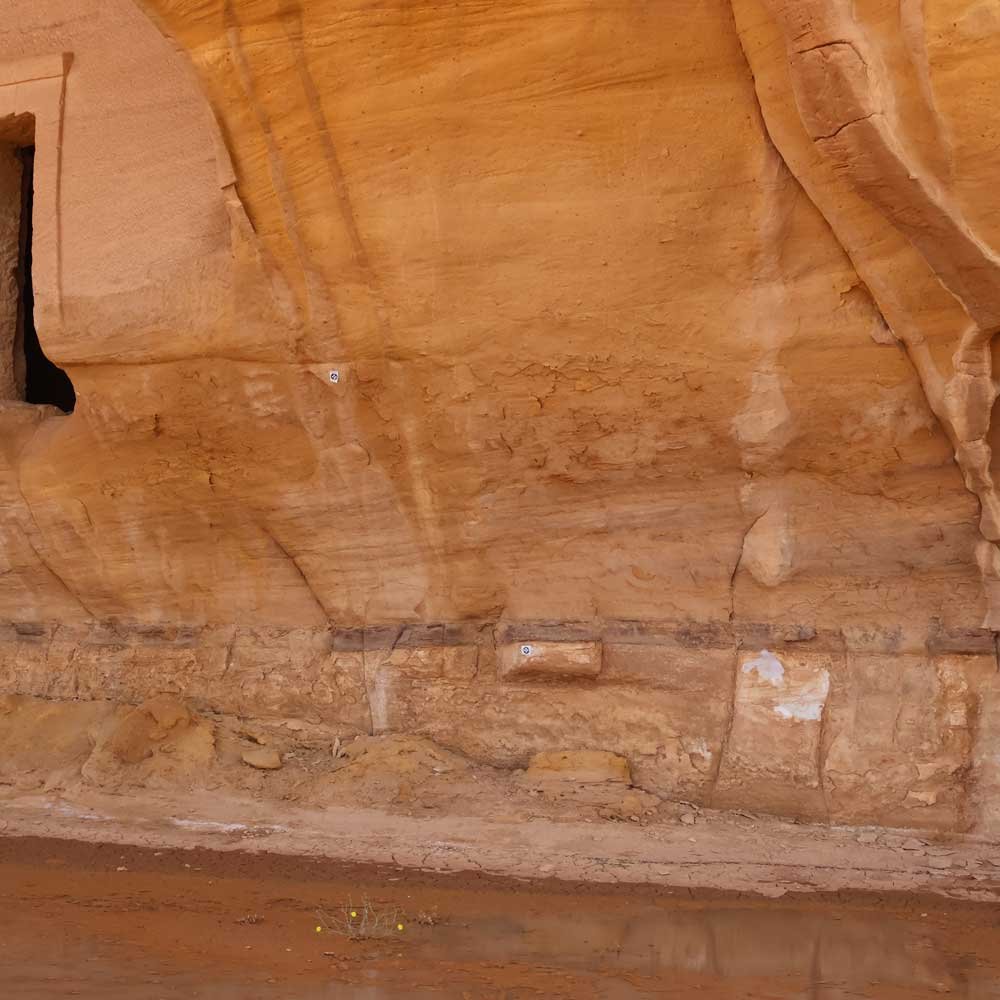

The archaeological site of Hegra is known for its tombs carved into sandstone, whose varying colors and qualities significantly affected both craftsmanship and conservation. The most elaborate parts used a light pinkish-beige sandstone, while harder, reddish-brown sandstone was used for simpler works. Geological challenges, like weak sandstone layers, capillary damp, and salt efflorescence, influenced tomb placement and design. Tomb locations were chosen for visibility and rock quality, sometimes requiring compromises for better materials. The quality of the stone dictated the size and complexity of the facades, reflecting social prestige and adapting to the site’s natural conditions.

The state of conservation of the Hegra Archaeological site

The archaeological site of Hegra presents a variety of conservation challenges that reflect the complexity and intensity of deterioration phenomena affecting its tombs. An analysis of the state of conservation of the tombs reveals clear signs of decay both on the facades and inside their structures. These issues vary depending on the nature and exposure of the tombs, but they exhibit similar trends.

The tombs, carved in sandstone, have withstood weathering for over 1900 years. However, their current state of conservation shows a range of complex deterioration factors that threaten their durability and integrity.

Among the main issues are detachments with different development (e.g., delamination, exfoliation, disintegration, and scaling), erosion, and several factors related to water, such as percolations, moist areas, and the transport and re-crystallisation of soluble salts as efflorescence and salt crusts. With regards to biological forms of degradation, several tombs are affected by the presence of shrubs and plants, as well as biological colonisation, including animal nests. Finally, some damages are attributable to the human actions; more precisely, these are the presence of engraved graffiti on the surface, often subsequently filled with a pinkish grouting, and mechanical damage due to the impact of bullets on the surface and frequently resulting in missing parts.

Erosion

The facades of many tombs display widespread erosion, particularly on the upper steps of the half-crowsteps and lower parts of the facade. This phenomenon caused the loss of original material and tool marks.

Detachment

The deterioration of the rock has caused the detachment of portions of material in several tombs, compromising the stability of the structures. This phenomenon is particularly evident beneath the thresholds and on the more exposed rock surfaces.

Disintegration

The rock surfaces of the tombs show signs of disintegration, especially in the lower areas of the facades and on the surfaces of the thresholds. This form of degradation is often linked to the presence of salt efflorescence and capillary rising damp.

Delamination

Delamination is evident on the external and often internal wall surfaces, running subparallel to the sedimentation plan. This phenomenon indicates significant structural issues and contributes to the loss of structural integrity.

Exfolation

The lower parts of many tombs show exfoliation related to capillary rising damp, water stagnation, and salt efflorescence.

Scaling

The internal walls and ceilings of many tombs exhibit scaling, which has led to the loss of surface stone. This phenomenon is often observable also in correspondence to the capillary rising damp front and the breaking surface of a missing part.

Crack

The tombs often display vertical and horizontal cracks, following the sedimentation plans of the rock itself. This form of degradation frequently led to the detachment of fragments.

Missing Parts

There are visible losses of decorative elements such as carved eagle heads, rims of acroteria, and small portions of material along the edges of the capitals and on decorative elements.

Efflorescence

White salt efflorescence, caused by water evaporation, are visible on many rock surfaces. The less visible subflorescence also contribute to deterioration and often leads to exfoliation and detachment.

Capillary Rising Damp

Capillary rising damp causes erosion, disintegration, cracks, and exfoliation of the rock surfaces, as well as the formation of incoherent deposits, including sand and soil, and white salt crusts in some areas.

Percolation

The runoff caused by the washing of surfaces by rainwater is visible along the facades, especially on the lateral pilasters and under the most protruding decorative elements, such as Egyptian cornices. They often develop as parallel vertical strikes.

Moist Area

Moisture stains indicate infiltration problems that contribute to disintegration and the formation of white salt efflorescence, particularly noticeable. This phenomenon is particularly visible at the lower parts of many tombs, where it exhibits capillary rising damp, water stagnation, and the consequent formation of salt efflorescence.

Alveolisation

Some areas show alveolisation, with cavities in the rock that amplify the deterioration. The rock itself appears particularly predisposed to the formation of alveoli of variable sizes and forms.

Deposit

Inside the tombs, there are incoherent deposits of sand and soil, and percolation of guano is visible beneath the funerary cells and overhanging areas where birds nest. Additionally, the solubilization and redeposition of the rock can provoke the formation of more coherent deposits, especially in correspondence to percolations.

Graffiti

Numerous graffiti, of various types, mark the facades of the tombs. They are located in areas such as near the entrances, cartouches, and the base of the tombs. Mortar interventions, sometimes of a different colour than the original rock, have been used to cover vandalic graffiti or natural chromatic differences in the surface.

Mechanical Damage

Mechanical damage is mainly caused by projectile impacts, visible in various areas of the tomb facades, but mostly located around the acroteria, presumably used as targets.

Discolouration and staining

Dark grey or brown stains are common on various surfaces of the tombs. They often extend horizontally and are located at varying heights from the ground.

Biological Colonisation

Dark areas on the rock surfaces indicate possible biological colonisation. These stains appear as biological substrates, and the presence of insect nests, such as wasps, may contribute to biological decay and aggravate disintegration issues.

Plant Vegetation

Plants and shrubs can cause mechanical damage, disintegration, and contribute to increased moisture. However, those located close to the massif appear to contribute to the reduction of the absorption of salts from the soil by the rock, using them as nutrients and at the same time assisting in the preservation of the façades.

Bibliography

Nehmé, L. (2015). Les Tombeaux Nabatéens de Hégra. Paris: Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres.

Nehmé, L. (2021). Guide to Hegra: Archaeology in the Land of the Nabataeans of Arabia. Paris: Skira.

Nehmé, L., Sachet, I., Arnoux, T., Bessac, J.-C., Dentzer, J.-M., et al. (2006). “Mission archéologique de Madâ’in Sâlih (Arabie Saoudite): Recherches menées de 2001 à 2003 dans l’ancienne Hijra des Nabatéens.” Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. Singapore: Wiley.

Nehmé, L., Villeneuve, F., Al Talhi, D., Al Anzi, A., Bouchaud, C., et al. (2011). Report on the Second Season (2009) of the Madâ’in Sâlih Archaeological Project. Paris.

Al Talhi, D., Nehmé, L., Villeneuve, F., Augé, C., Benech, C., et al. (2014). Report on the Third Excavation Season (2010) of the Madâ’in Sâlih Archaeological Project. Riyadh: Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities.

Nehmé, L., et al. (2014). Report of the Fifth Season (2014) of the Madâ’in Sâlih Archaeological Project. Paris: Orient & Mèditerranèe.

Alhaiti, K., Bouchaud, C., Delhopital, N., Durand, C., Fiema, Z. T., et al. (2016). Madâ’in Sâlih Archaeological Project. Report on the 2015 Season. Paris.

Nehmé, L., Bouchaud, C., Delhopital, N., Durand, C., Égal, F., et al. (2020). Report on the 2018 and 2019 Seasons of the Madâ’in Sâlih Archaeological Project. CNRS.

Nehmé, L. (2004). “Explorations Récentes et Nouvelles Pistes de Recherche Dans l’Ancienne Hégra des Nabatéens, Moderne Al-Hijr/Madâ’in Sâlih (Arabie du Nord-Ouest).” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Paris: Diffusion de Boccard.

Nehmé, L., al-Tahi, M.D., Villeneuve, F. (2008). “Résultats Préliminaires de la Première Campagne de Fouille à Madâ’in Sâlih en Arabie Saoudite.” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Paris: Diffusion de Boccard.

Margottini, C., Spizzichino, D., Boldini, D., Lusini, E., Crosta, G., Frodella, W., Beni, T. (2022). Atlas of the Geomorphological Processes and Rock Slope Instabilities Affecting the AlUla Archaeological Region.

Gallego, J.I., Margottini, C., Spizzichino, D., Boldini, D., Abul, J.K. (2022). Geomorphological Processes and Rock Slope Instabilities Affecting the AlUla Archaeological Region.

Jaussen, A., Sauvignac, R. (1914). Mission Archéologique en Arabie II, El-‘Ela, D’Hégra a Teima, Harrah de Terguk. Paris: Société des Fouilles Archéologiques.

Nehmé, L., Amoux, T., Bessac, J.-C., Braun, J.-P., Courbon, P., Dentzer-Feydy, J., Rigot, J.-B., Sachet, I. (2006). “Report on the 2003, Third Season, of the Saudi-French Archaeological Project at Madâ’in Sâlih.” ATLAL, The Journal of Saudi Arabian Archaeology. Riyadh: Deputy Ministry of Antiquities and Museums, Ministry of Education.

Nehmé, L. (2005). “Towards an Understanding of the Urban Space of Madâ’in Sâlih, Ancient Hegra, through Epigraphic Evidence.” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, vol. 5. Oxford: Archaeopress.

RCU Archive (2023). The Diwan 20231109. Digital media.

RCU Archive (2023). RCU-IGN17. Digital media.

RCU Archive (2023). RCU-IGN110. Digital media.

Healey, J.F. (1993). The Nabataean Tomb Inscriptions of Mada’In Salih. Oxford: Oxford University Press.